By Mark Will-Weber

The first real stars of the Berwick Marathon were runners from the Carlisle Indian School.

At the 1909 race, their war whoops reverberated in the chilled autumn air at the start on Market Street—and less than an hour later, some of them left bloody moccasin prints in the snow as they trudged to the finish.

The spectators, mostly town people, were absolutely fascinated by them.

They were the long-distance running teammates of Jim Thorpe—who in a few years was to become one of the most famous athletes on the planet when he won the Decathlon event at the Stockholm Olympics Games. But in late November of 1909 it was these Native American thin-clads who were brought to Berwick, Pennsylvania, to run a Thanksgiving Day footrace over a rugged and rutty nine-mile course. Most of the roads outside of town were still unpaved (and, in the 1909 event, frozen), and those Carlisle runners who wore deerskin moccasins wore them as they hammered out the nine miles.

While the inaugural event in 1908 had been a local (and somewhat plodding affair), race director Chiverton “Chiv” MacCrea—a man with a touch of P.T. Barnum-like showmanship in his blood—brought in some top “thoroughbreds” the following year. Chiv MacCrea was an acquaintance of Glenn “Pop” Warner, who in addition to being a nationally renowned football coach at the Carlisle, also dabbled as the head coach of track and field. And it was this connection that brought distance running greats—-Louis Tewanima, a Hopi from Arizona, and Mitchell Arquette, a Mohawk from upstate New York—to the starting line in 1909.

The diminutive Tewanima was already relatively well-known, having placed 9th in the Olympic Marathon in London in 1908, and the well-muscled Arquette was considered the most-likely man to keep close. The “smart money” (and lots of locals wagered on the race, especially in those early days) was not led astray, as little Tewanima scooted in first in a time of 54 minutes, 16 seconds, and Arquette finished a strong second, less than 200 meters behind. In fact, five of the first half-dozen finishers represented the Carlisle contingent, with only Canadian entry Don McQuaig (5th) breaking up a complete sweep.

It was the first of what was to be a trio of victories (1909, 1910 and 1911) for Tewanima. Arquette was a close second in 1910 (just 8 seconds back) and third in 1911. Tewanima went on to snag a silver medal in the 1912 Olympic Games, behind rising Finnish star Hannes Kohlehmainen. After the 1911 race, neither Tewanima or Arquette returned to Berwick again. Both eventually went back to their respective reservations—a choice that whites in the Indian School hierarchy sometimes referred to derisively as “returning to the blanket.”

It should be noted that the vast majority of Native Americans at the Carlisle Indian School were there against their will. They were sent there to learn a trade, the English language, convert to Christianity, and—if they had the athletic ability—represent the institution in sporting competitions. The enthusiastic curiosity surrounding their appearance in Berwick was also tempered by some lingering suspicions; the Native American athletes were always accompanied by an overseer and essentially were kept under lock and key in the St, Charles Hotel when they weren’t running.

Years later, Berwick native Ruth Fulmer acknowledged that the Carlisle runners drew close scrutiny from race day fans. Writing in a local newspaper article titled “Berwick in the Making” she wrote:

“It seems to me that there was a peculiar satisfaction in seeing Indians win those early races. The skinny, narrow-chested Tewanima was nothing to attract feminine attention as he stood shivering in the cold wind, waving his long, thin arms, but he managed to do quite well for himself, you may recall. Arquette, one of his running mates, was a bronze Adonis compared to him. The High School girls all gazed at Arquette with the same intensity that today’s girls would gaze at Clark Gable, but he never even saw us!”

Various New York City Club runners dominated the Berwick race from 1912 through 1914, but by 1915, the top-notch “Flying Finns” were on the scene and—like the Carlisle Indians—something of a novelty.

Hannes Kohlehmainen—arguably the top runner in the world during the First World War era—had emigrated from a tumultuous Europe to New York City. He won the Berwick race three straight times (1915, 1916, 1917). Quietly confident (he has, after all, set the world record for 10,000 meters in the Stockholm Games in 1912), Kohlehmainen was said to have soothed any pre-race nerves by shooting pool at some local parlor.

A local lad—Penn State runner John “Blondy” Romig from nearby Wapwallopen—a tiny village situated on the banks of the Susquehanna River—won the 1920 event, wisely wearing track spikes to better negotiate icy road conditions. But then Ville Ritola, another Finnish star who would go on to win Olympic medals, snagged back-to-back victories in 1921-22.

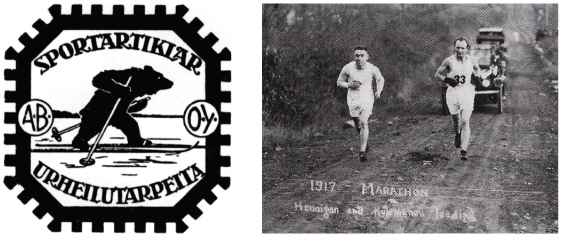

(On right) Stride for Stride: Jimmy Hennigan (left) and Hannes Kolehmainen (33) battle over Berwick’s stone-strewn roads in the Flying Finn’s final appearance in 1917. (Photo courtesy of Harry’s Sports)

Canadian runners are a unique part of Berwick race history, and the Maple Leaf men dominated the event in the late 1920s and through most of the 1930s. Cliff Bricker was the first ever Canadian runner to win at Berwick (1926 and 1927), followed by Will McCluskey of Toronto, a surprise winner in 1932.

In between Bricker’s wins and the next wave of conquerers from The Great White North, runners from Gotham proved that they still had what it takes to tame the hills of Berwick, as Brooklyn Harriers went back-to-back—Phil Silverman in 1928 and August “Gus” Moore, the first African American to strike victory in the storied footrace, in 1929.

But then Scotty Rankine—who represented Canada in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games—rattled off five straight victories (1933 through and including 1937). He was popular with the knowledgeable Berwick spectators and induced to speak after his fifth title.

“I’m not getting a kick out of winning as I used to,” Rankine quipped, “but I do get a kick out of coming to Berwick. I like it here. Maybe now that I have won five times in a row you had better pension me.”

If the 1930s were dominated by Rankine, it was two-time Boston Marathon champion Johnny Kelley who called the tune—think jaunty Irish jig—in the early 1940s. In his memoir Young at Heart Kelley made mention that he won 22 diamond rings during his career—and where the bulk of those prizes came from would not be a hard mystery to solve for Berwick buffs. Kelley won a grand slam of Berwick races—1942 through and including 1945.

Earlier in the decade, another former Boston Marathon champ—the colorful, free-spirited Ellison “Tarzan” Brown—snagged the 1940 event. Brown—a Narragansett Indian from Rhode Island—drummed up all the old hoopla regarding Native American runners; something of a nostalgic shout out to the days of Tewanima and Arquette.

Brown wrote to race director MacCrea that he was “in excellent form and confident of winning”—and then he backed it up, despite snowy, slick and windy conditions. Brown had to beat Kelley and also three-time Boston Marathon champ Les Pawson to secure the victory.

A lot of runners who grew up in South Jersey used to talk about this guy Browning Ross—an “old school” runner turned race director who staged dozens of events and often gave out a motley array of awards and prizes from the trunk of his car.

But the youngest among them might not have realized that Ross also was one of the best American long-distance runners in the pre-boom era. He ran for Coach Jim “Jumbo” Elliott at Villanova, but even then had an affinity for road races and sometimes would try to sneak in a few during the season. That didn’t sit well with the legendary coach (who dismissively referred to such races as “street runs”) and when, according to one story, he saw Ross’s name in the papers for winning one, threatened to send him “back to the tomato farms” of South Jersey if he did it again.

Ross went on to finish 7th in the 1948 Olympic 3000-meter steeplechase in London and also had several Pan American gold medals to his credit.

But he also was quite proud of his record (still unequalled) of ten Berwick crowns! He won the race in 1946, 1947, and 1948. Penn State star (and fellow 1948 Olympian) Curt Stone broke up Ross’s streak in 1949, but then “Brownie” racked up seven more titles from 1950 through 1956. He once told Hal Higdon (writing for The Runner in 1983) that what we now call “The Run for the Diamonds” was his favorite race.

“They’d pay my expenses. Everybody in town turned out. I won it ten or eleven times. First prize was a diamond ring worth $130, or so they claimed.”

Mark Will-Weber—a former senior editor/writer at Runner’s World magazine—is the author of “Run for the Diamonds: 100 Years of Footracing in Berwick, Pennsylvania” and the creator of “The Quotable Runner.” He has coached at Moravian College and Lehigh University, with high school stints at Palmerton, Freedom, and Liberty. He is presently a part-time coach at Lehigh University.

Categories: Features

Thank you for publishing Mark’s excellent piece on the Berwick marathon. I didn’t realize all the world famous runners races there over the last century.

I appreciate this historical article.

Ed

On Wed, Jan 3, 2024 at 12:37 PM Runner’s Gazette < comment-reply@wordpress.com> wrote:

LikeLike

Sir, Any thoughts of turning this interesting narrative into a screenplay. Seems to contain several intriguing story lines!

Berwick native and 5-time participant, Dave Major

LikeLike